- May 11, 2008

- 22,317

- 1,426

- 126

I recently saw this documentary about bacteriophages.

Phage- The virus that cures

The link is dead.

For to see the video, press this link :

forums.anandtech.com

forums.anandtech.com

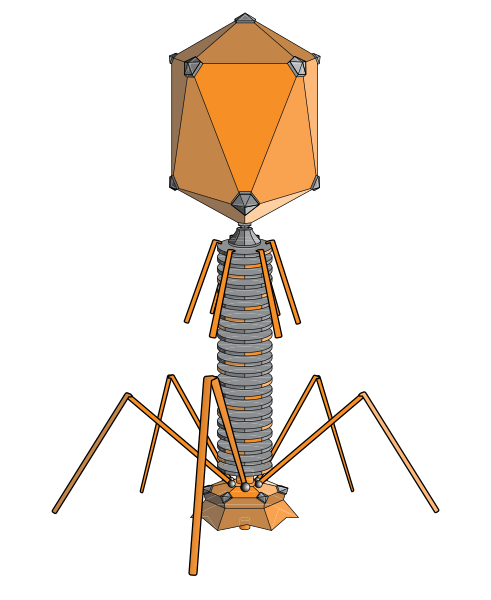

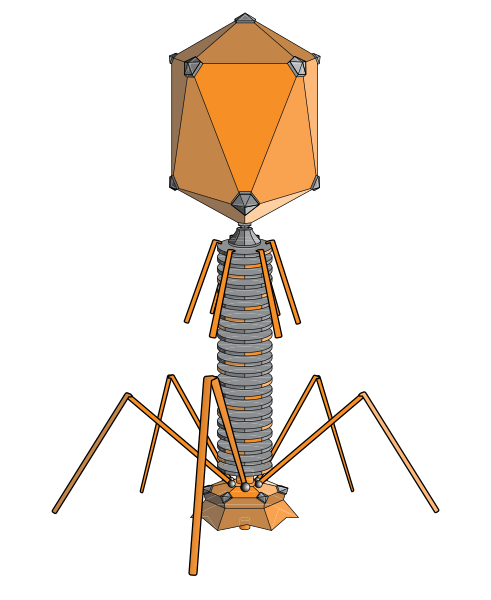

Bacteriophages

Horizontal gene transfers

You ask perhaps why i posted this message, well i ask for opinions.

Long ago i bought a scientific american magazine (i think it was). There was some information about the possibility of horizontal gene transfers.

My Opinion is that through vertical gene transfers (aka offspring through sexual reproduction) and evolution a complex lifeform can loose genes. But with horizontal gene transfers a complex lifeform can gain genetic code. And not just a few basepairs but an entire sequence.

EDIT START : I think that it is entirely possible that this gene swapping can also occur between bacteria and viruses and cells of complex lifeforms. Most of the time our error detection/ error correction together with self destruction methods (cell apoptosis) and our immune system combat any change in dna code but radiation( or even cosmic radiation) and toxic materials can cause mailfunction to these error detection/correction systems and our immune system.

Cell apoptosis

EDIT END

Would this statement hold ?

Phage- The virus that cures

The link is dead.

For to see the video, press this link :

Page 14 - Phage , the virus that cures

Page 14 - Seeking answers? Join the AnandTech community: where nearly half-a-million members share solutions and discuss the latest tech.

Bacteriophages

Horizontal gene transfers

You ask perhaps why i posted this message, well i ask for opinions.

Long ago i bought a scientific american magazine (i think it was). There was some information about the possibility of horizontal gene transfers.

My Opinion is that through vertical gene transfers (aka offspring through sexual reproduction) and evolution a complex lifeform can loose genes. But with horizontal gene transfers a complex lifeform can gain genetic code. And not just a few basepairs but an entire sequence.

EDIT START : I think that it is entirely possible that this gene swapping can also occur between bacteria and viruses and cells of complex lifeforms. Most of the time our error detection/ error correction together with self destruction methods (cell apoptosis) and our immune system combat any change in dna code but radiation( or even cosmic radiation) and toxic materials can cause mailfunction to these error detection/correction systems and our immune system.

Cell apoptosis

EDIT END

Would this statement hold ?

Last edited: